Get Information

We have to talk about flying!

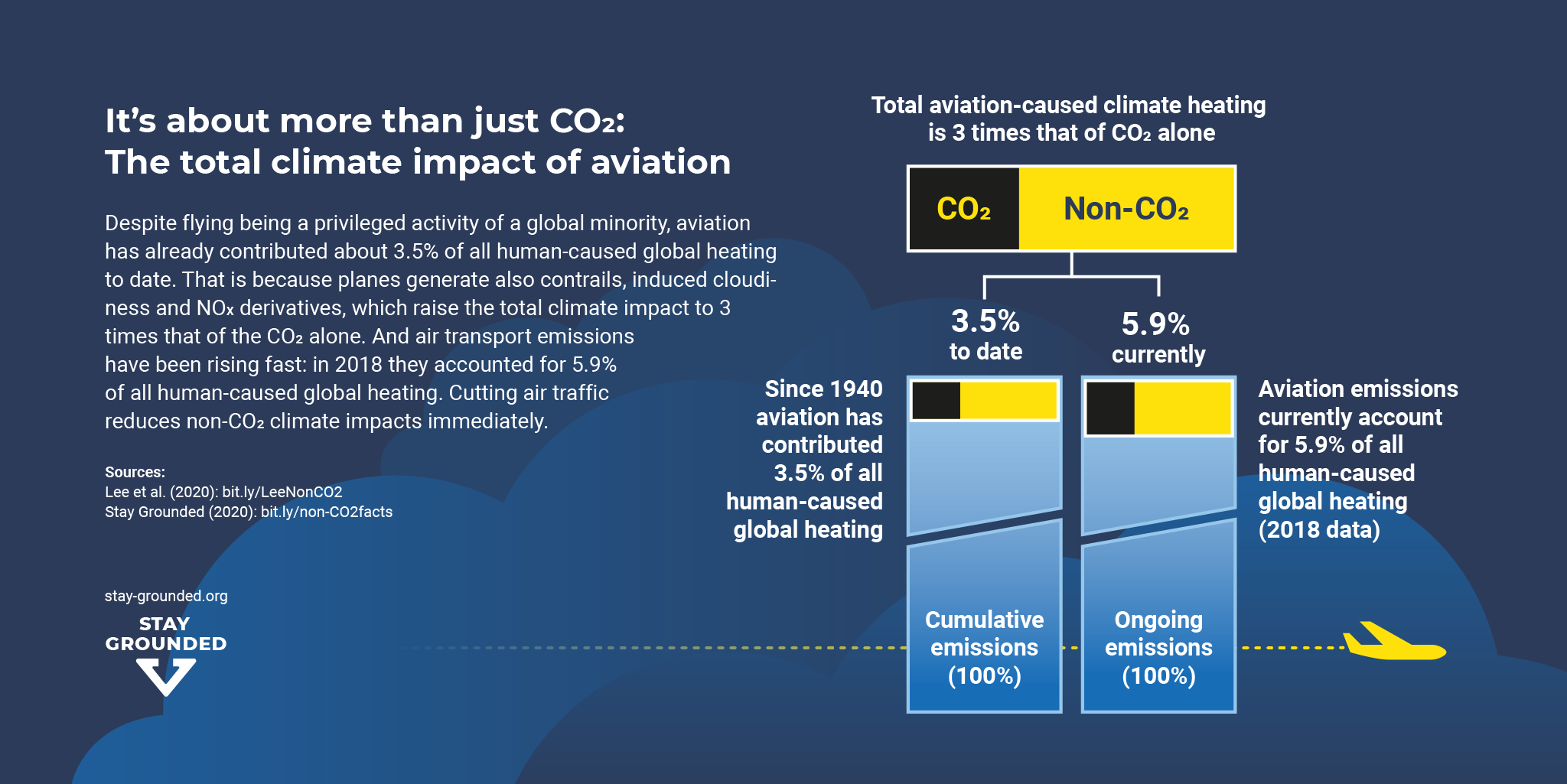

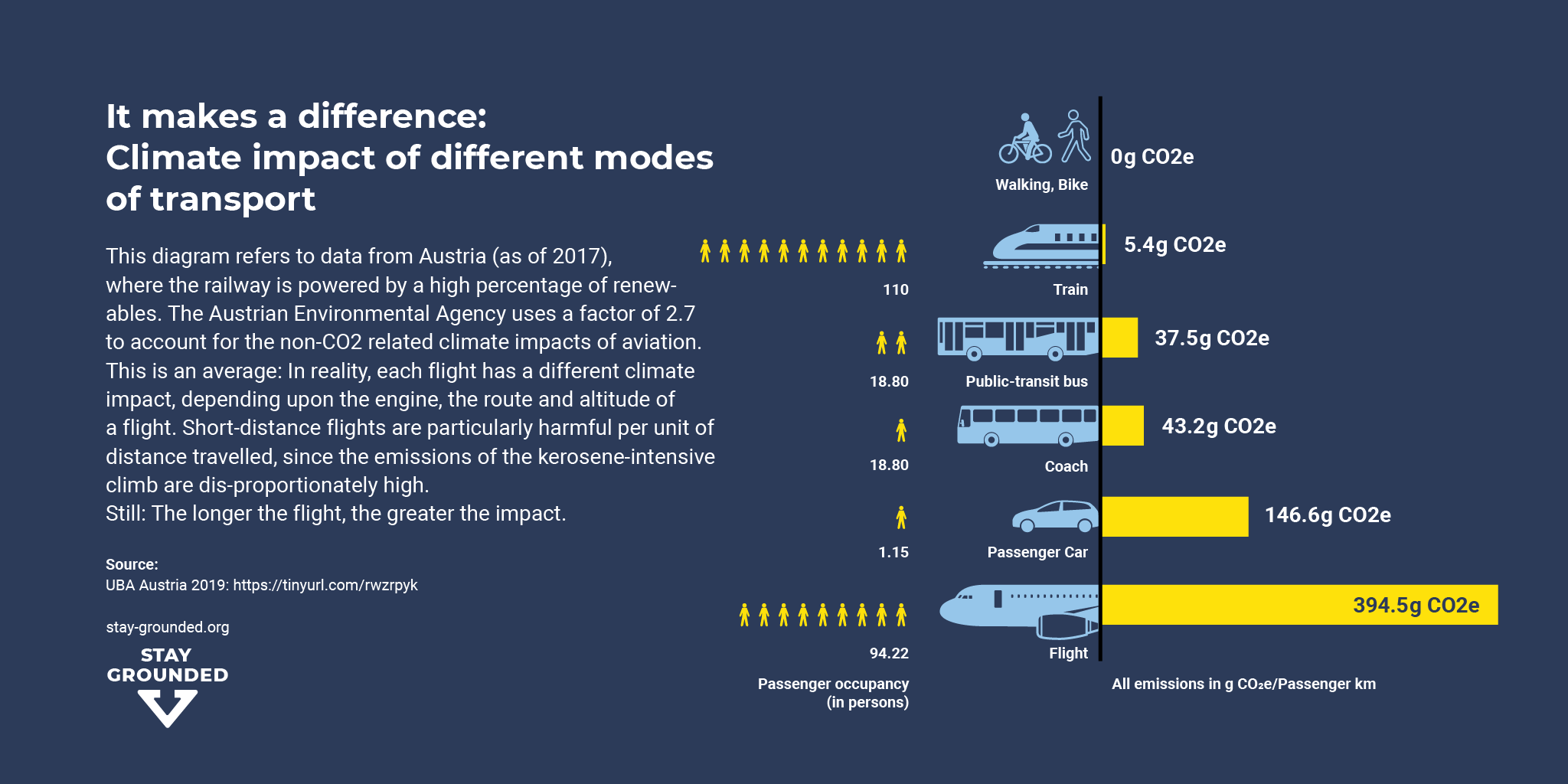

What is the climate impact of aviation?

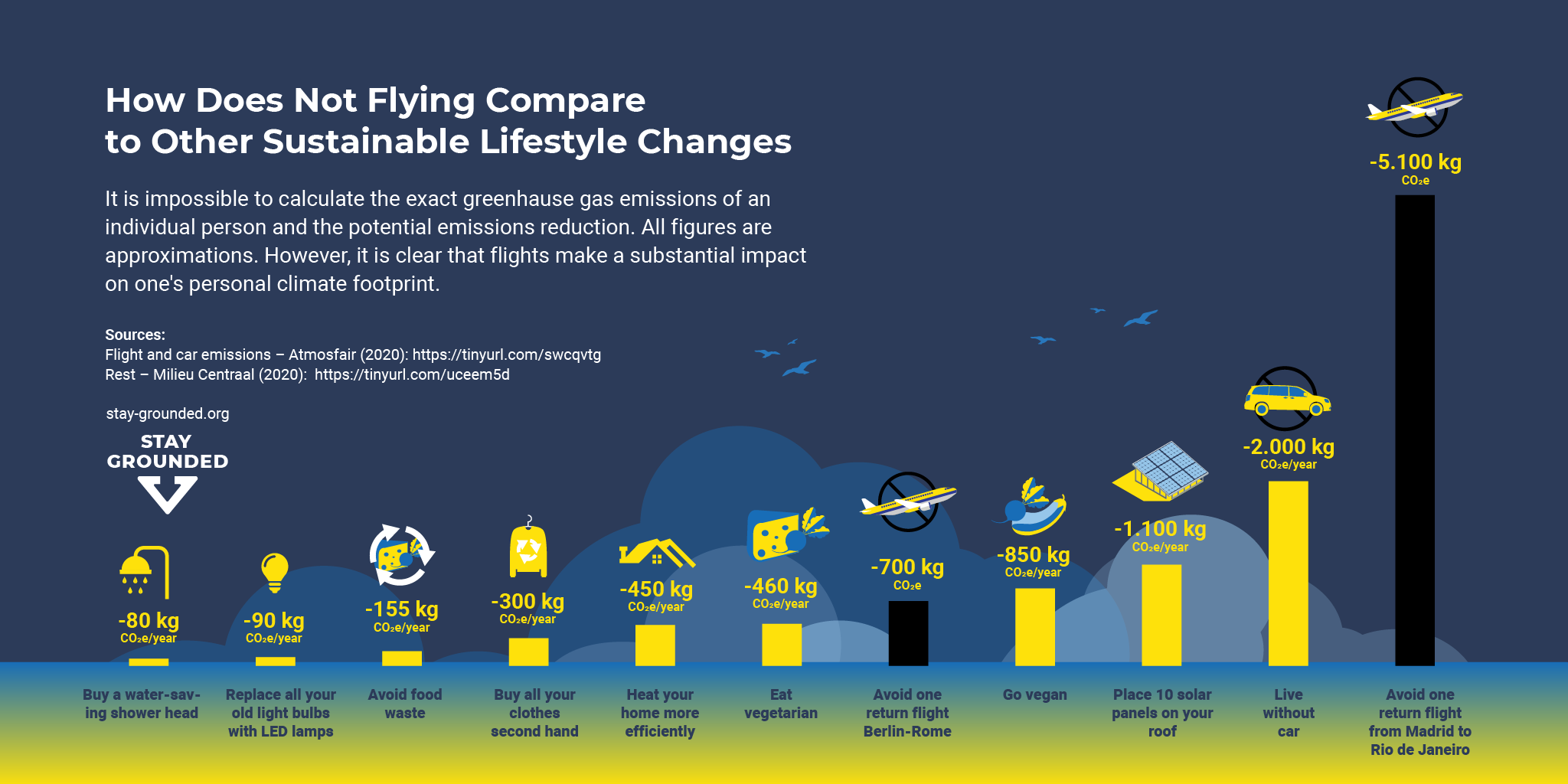

How bad is flying for your carbon footprint?

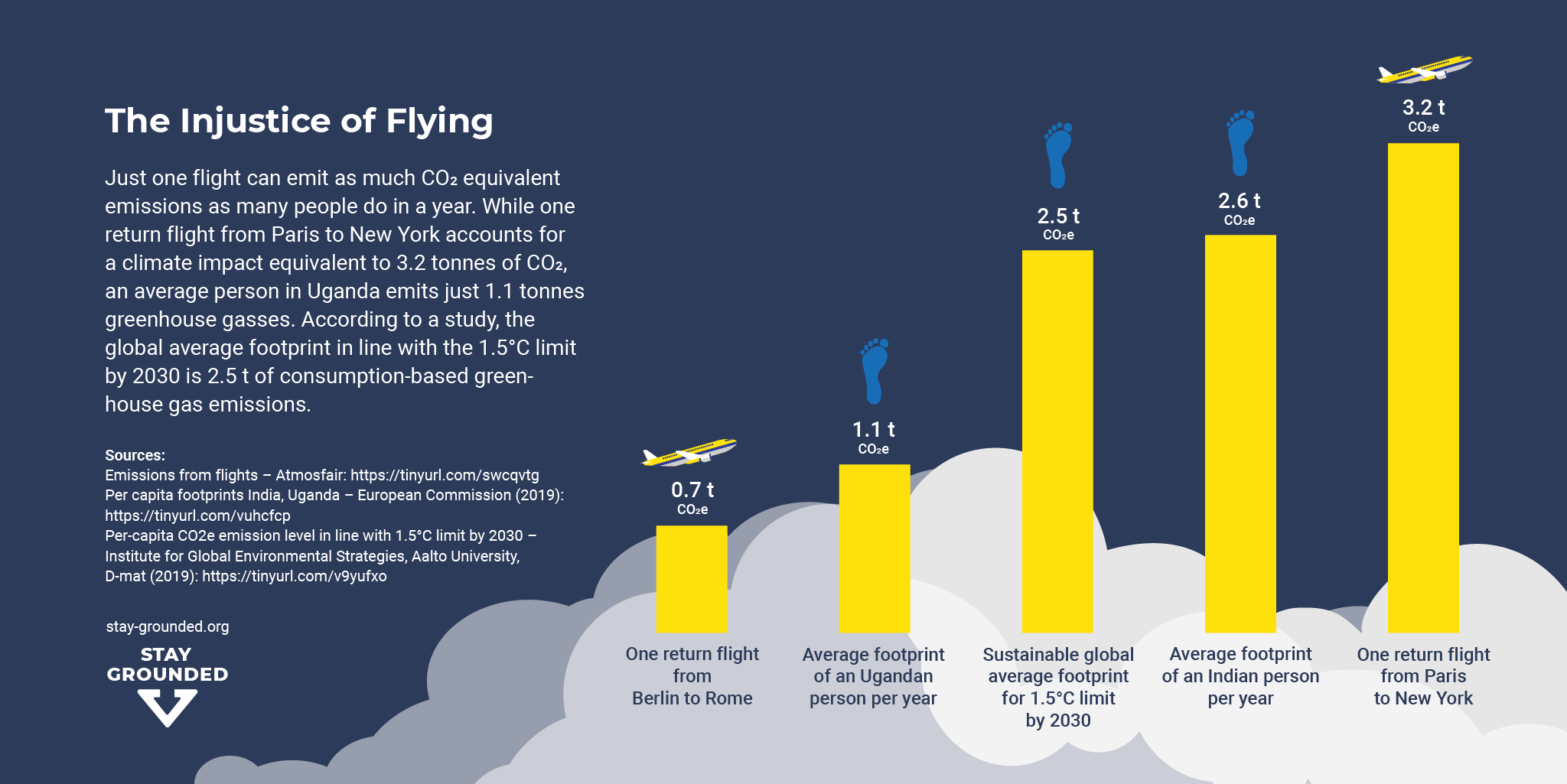

How unjust is flying?

Why is offsetting not the solution?

Is green flying possible?

Why is aviation’s climate impact insufficiently regulated?

Why is flying so absurdly cheap?

What's the impact of military aviation?

Reliable figures on the subject of military aviation emissions remain scarce and fragmented.

Which political changes do we need?

What happens when airports increase?

What is the climate impact of aviation?

Stopping the climate crisis is the biggest challenge humanity has ever faced.

How bad is flying for your carbon footprint?

Spoiler: It’s very bad.

For every tonne of carbon dioxide one person emits, three square metres of Arctic summer sea ice disappear. This means that by taking a transatlantic flight, one passenger is responsible for the loss of at least six square meters of ice. But it’s not just about sea ice, also glaciers on land are melting. And with a projected sea level rise of more than one meter by the end of the century, every meter of ice counts …not only for the penguins, whose habitat and population is declining rapidly.

How unjust is flying?

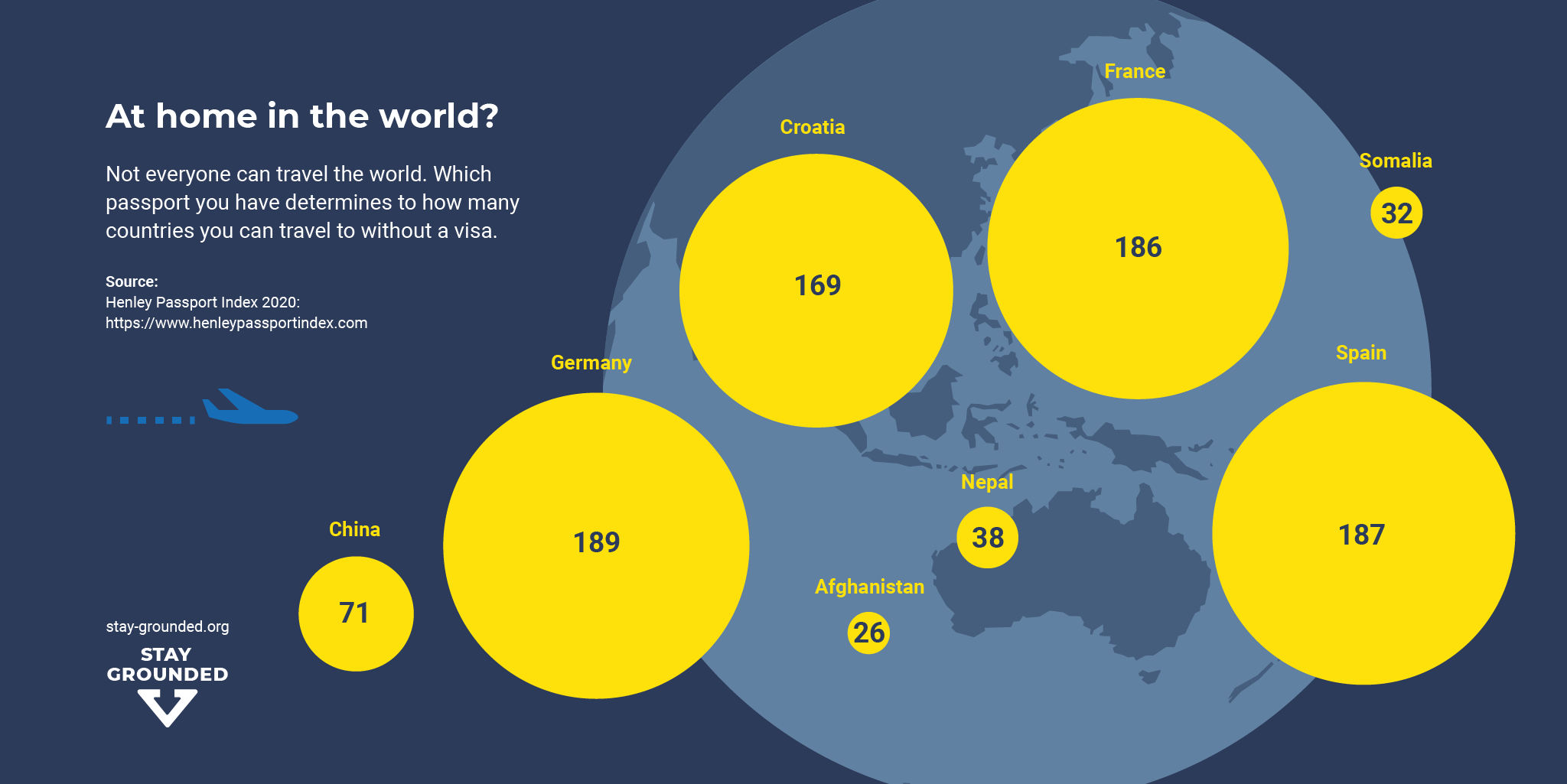

Air traffic is a major obstacle to climate justice. While to Western Europeans, it might seem normal to fly, this “normality” has only existed in the last decades, and is still rare on a global scale. It is hard to find exact numbers, but estimations say that about 10%, or between 5 and 20%, of the global population has ever taken a flight. Lots of people cannot afford flying, or are not allowed to do so because of restrictive migration policies.

There’s also a big difference to be made between the reasons for flying. So should a businessman on his monthly flights to his Tuscan villa be treated the same as someone who flies every second year to visit close family on another continent? There are solutions to this injustice issue – find out more about a frequent flyer levy and other measures.

Why not just offset your flight emissions?

“Flying isn’t a problem if you pay a bit more to compensate the emissions.” That’s the message airlines tell customers. Many organisations trying to implement more sustainable travel policies recur on offsetting. But that’s not all: the only existing international agreement covering aviation’s CO2 emissions, called CORSIA, builds on offsetting. What’s behind these offsets?

What are offsets?

Offsetting projects are mostly located in countries of the Global South. Many of them are hydroelectric projects, claiming to prevent production of energy from fossil fuels. Also forest conservation projects, operators of tree plantations, or organisations that distribute climate-friendly cooking stoves to women in rural parts can sell offset credits.

What are the problems with offsetting?

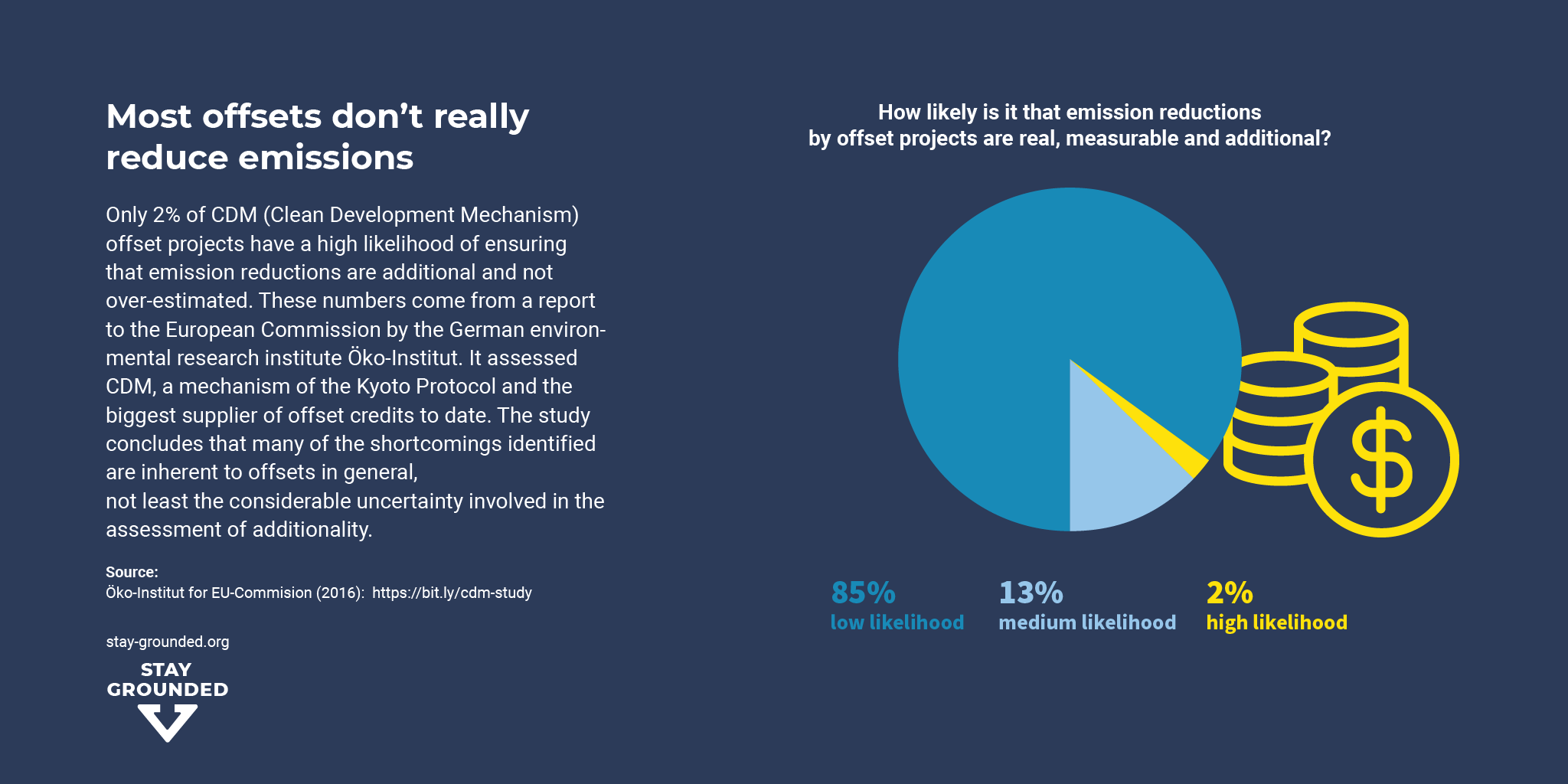

1. Offsets fail to reduce emissions

Studies show that a majority of projects miscalculate their savings. Öko-Institut investigated the effectiveness of existing offsetting projects of the UN and concluded that only 2% of the projects have a high probability of resulting in additional emissions reduction. This way, emission reductions would have occurred also without paying the offset, for example because a hydropower plant would have been built anyway. In the case of trees, they need years to grow enough to reabsorb the carbon from your flight. It is hard to guarantee they will be left standing long enough to counteract your flight.

Since it’s cheaper to offset in the Global South, this is where most projects are located. They often lead to local conflicts or land grabbing. This is especially the case with land or forest-based projects like REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation). Often, small-holders and indigenous people are restricted to use the forest in their ancestral way in order to store the predicted amount of carbon in the trees. Ultimately, offsetting is exposed as carbon colonialism by many indigenous groups.

3. Offsets are a modern sale of indulgences

Offsetting enables a small share of the world population to fly indefinitely with a supposedly clear environmental conscience. Some therefore compare the trade in compensation credits with the selling of indulgences by the Catholic church. Money could buy absolution from sin – but of course didn’t prevent the sin in the first place. The money could be used to build cathedrals and keep the Vatican going. The current Pope Francis has a more sophisticated view on today’s offsetting. He says: “Aircraft pollute the atmosphere, but, with a small part of the cost of the ticket, they will plant trees to compensate for part of the damage created. …This is hypocrisy!”

4. Offsetting diverts the attention from real solutions

Some have argued that if we make offsetting possible as a ‘last resort’, and try to offset emissions locally, this would be better than doing nothing. However, the fact remains that offsetting then becomes a license to pollute and help preserve the status quo. In this way, offsetting prevents the necessary fundamental changes of our mobility system.

So if you really want to give money away, rather support this campaign than paying it to offsetting companies.

Read more:

- Report by Stay Grounded (2017): The Illusion of Green Flying

- Transport & Environment Article (2020): Airline Offsetting is a Distraction

- Fern’s campaign against aviation offsetting: https://www.fern.org/climate/aviation/

- Report by the Climate Justice Alliance (2017): Carbon Pricing. A Critical Perspective for Community Resistance

- Study by the Global Forest Coalition (2021): Arauco’s Valdivia biomass power station: carbon emissions and conflicts with Indigenous communities in Chile

Is green flying possible?

Faced with growing critique and the need to defend their climate damaging growth plans after the COVID-crisis, the aviation industry is strengthening their narratives.. In greenwashing campaigns, they announce their intention to make aviation “net zero” in 2050. Technological efficiency, alternative fuels and offsetting play a big part. The problem is: Growth of air traffic is not questioned, and the proposed solutions are far from tackling the problem of aviation climate impact.

In February 2020, the biggest aviation emitter in Europe, Ryanair, was sanctioned by a court for misleading claims that it was a green airline. This was a clear ruling – but most of the time, without knowing details, it’s hard to decipher the industry’s myths.

In our latest Fact Sheet Series on Greenwashing, we debunk common myths and misconceptions.

Energy efficiency: Too little

By using better technology in new aircraft, efficiency gains of around 1.3% per year seem possible. However, efficiency gains usually make flying cheaper, and therefore encourage even more people to fly. Given that the industry’s expected annual growth rate is currently 4% and recently growing by 7%, savings from efficiency gains barely scratch the surface.

For more information see our Fact Sheet on Efficiency Improvements.

Biofuels: A Problematic Alternative

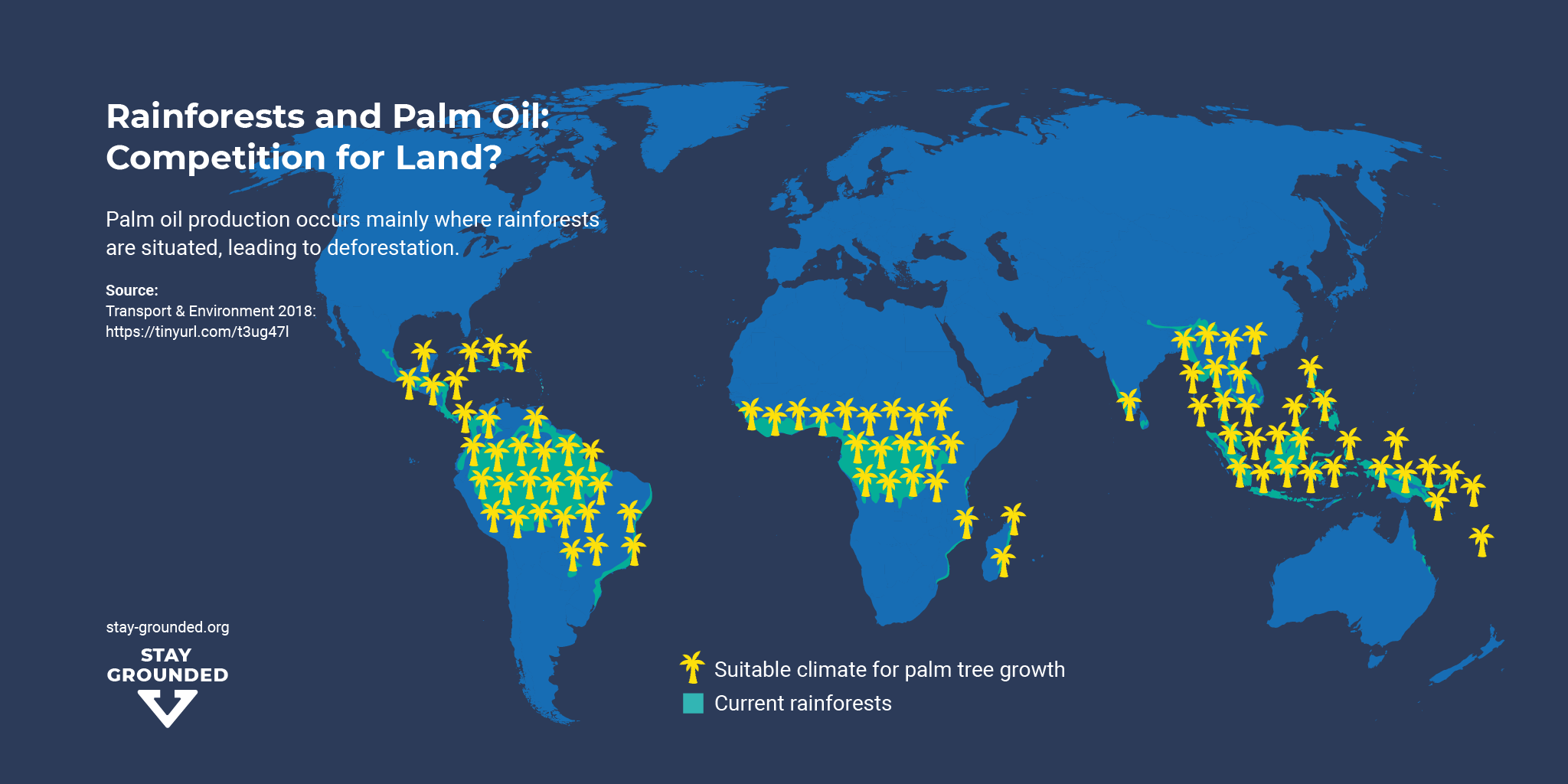

The industry plans to replace part of their fossil kerosene with biofuels. Biofuel scale up has been promised for more than a decade but this has not materialised. Today, biofuel accounts for less than 0,01% of all aviation fuel used. This is very little – which might be actually good news. Even though the industry says it will use only second generation biofuels from waste, first generation biofuels made from crops have not been ruled out. These are proven to cause very serious environmental and social impacts such as biodiversity loss, rising food prices and water scarcity. Palm oil would be the most viable option, even though a study by the European Commission concluded that palm oil biofuels release at least three times more greenhouse gas emissions than the fossil fuels they replace.

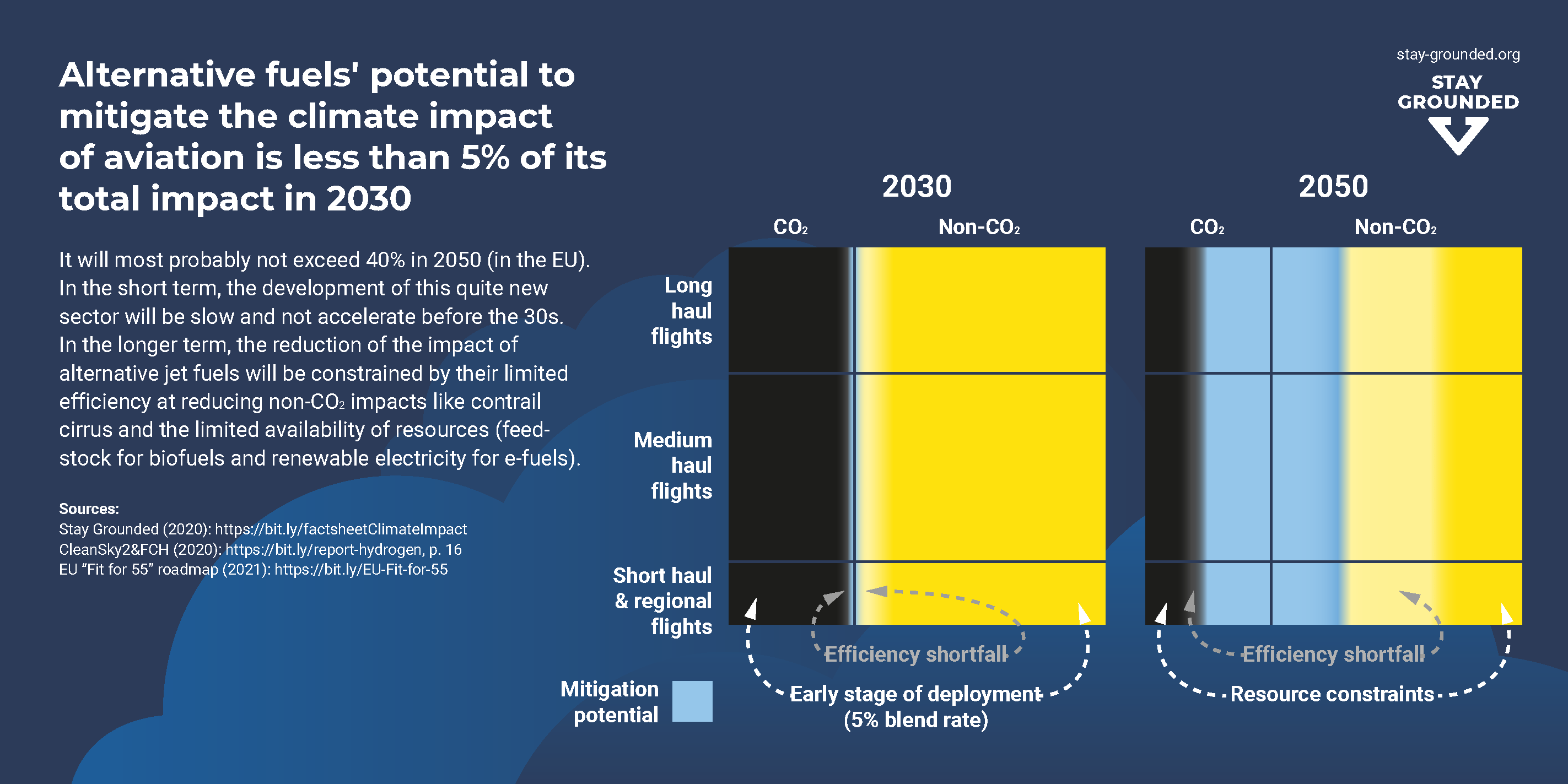

On the other hand, second generation biofuels feedstocks are available only in limited quantities. Finally biofuels would only partially reduce the non-CO2 emissions, which account for a big share of aviation’s climate impact.

For more information see our Fact Sheet on Biofuels

Electric Airplane: Too Small and Too Short Range

Electric aircraft likely to be certified this decade will be very small and serve only for very short flights. But those can easily be replaced by ground transport in most cases which are more efficient..

For more information see our Fact Sheet on Electric Flight

Hydrogen: Too Late and Not Zero

Hydrogen will not be viable for medium and long-haul flights before 2050. Until then, only the regional and short-haul market could be converted, a large part of which can be substituted by road or rail. But before hydrogen aircraft becomes a reality, many problems must be solved, especially in the field of safety.

For more information, see our Fact Sheet on Hydrogen flight

E-Fuels: A Dangerous Hope

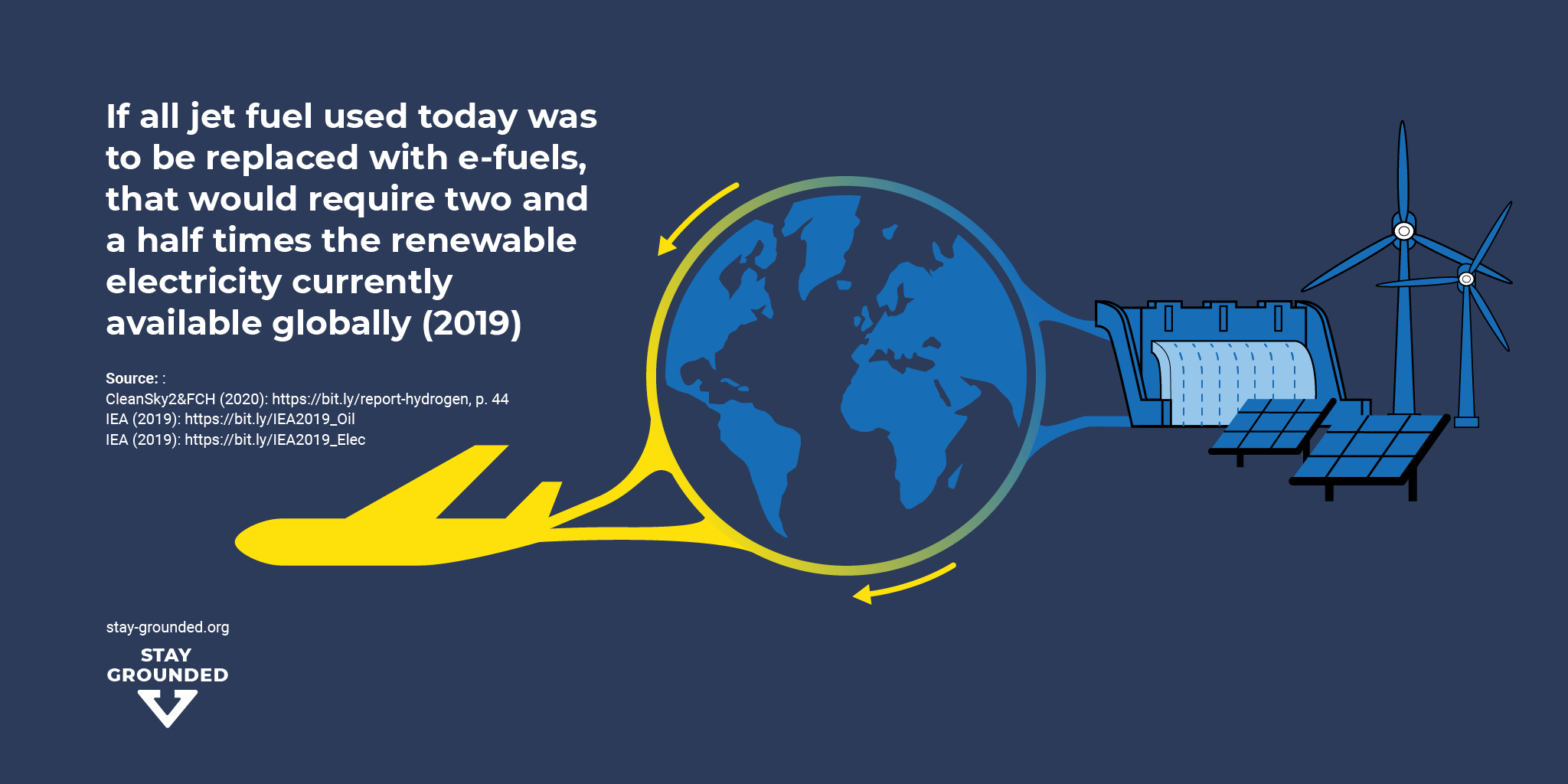

Synthetic fuels made from electricity (Power to Liquid) are technically feasible, but there are almost no facilities to produce them yet. Several decades of heavy investment would be needed to scale up production. And converting electricity to fuel is an energy intensive process. The problem is: we are a long way from even producing enough renewables for transport on the ground, manufacturing, agricultural production or heating. If all planes were to fly with e-fuels today (in 2019), this would consume about two and a half times the renewable electricity currently available globally. And also, most of the non-CO2 climate effects of flying would remain – and these are about two times the CO2 emissions today.

For more information see our Fact Sheet on E-Fuels

Rerouting flights: mitigating the effects from contrails

A rather promising approach is to change the routes of some long-haul flights: This could mitigate the non-CO2 climate heating effect of contrails, which are cirrus clouds that form under special atmospheric conditions, depending on location and time. It mostly affects transatlantic night flights. Contrails have a similar climate effect as CO2 – limiting them therefore makes a lot of sense. Nevertheless, changing the routes will go at the expense of more fuel burnt. This therefore needs to go along with a reduction of flights.

Offsetting emissions: shifting the problem instead of tackling it

Given that there are no technological solutions in the near future, the solution presented most often by the aviation industry is offsetting: compensating emissions through buying offset credits. Find out here why this option won’t solve the problem, causes unintended consequences and could lead to even bigger problems.

Read more:

- Transport & Environment Article (2020): Airline Offsetting is a Distraction

- Fern’s campaign against aviation offsetting: https://www.fern.org/climate/aviation/

- Report by the Climate Justice Alliance (2017): Carbon Pricing. A Critical Perspective for Community Resistance

- Report by Stay Grounded (2017): The Illusion of Green Flying

- Scientific Article (2016): Are Technology Myths stalling Aviation Climate Policy?

Why is aviation’s climate impact insufficiently regulated?

In the Paris Agreement, as in its predecessor, the Kyoto Protocol, international aviation, accounting for about 65% of civil aviation emissions, is not covered, and also domestic aviation not explicitly mentioned either. Instead, the United Nations agency ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organisation) is responsible.

In 2016, 18 years after it received the mandate to do so, ICAO presented its climate plan for aviation, called CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation). This CORSIA scheme is designed to cap aviation emissions from 2021 onwards and allow “carbon-neutral growth”. This is to be achieved mainly through offsets, i.e. by compensating emissions through supposedly climate-friendly projects. Read about the problems involved with offsetting here.

CORSIA involves several other problems: first, only a small part of the emissions is covered at all. The first years are voluntary, and only 81 states will participate. Second, the programme only covers the growth in emissions from 2021 onwards (until 2035), i.e. the emissions that will be added to the level of 2020 every year from that time onwards. But already now, aviation emissions’s are too high and would need to be reduced. Third, the non-CO2 effects of aviation are not accounted for, meaning that at least half of the climate impact is ignored. Fourth, CORSIA does not include emissions from domestic flights. Fifth, CORSIA could possibly legally impede stronger national aviation regulations. Even further flaws, loopholes and missing safeguards lead to many civil society groups demanding to stop CORSIA.

In Europe, flights are theoretically covered by the EU Emissions Trading System. However, a tonne of CO2 costs far too little in this scheme to make a real difference. In addition, airlines are allocated a large proportion of emission rights free of charge. And international flights from and to the EU are completely excluded.

The lack of regulation of the aviation sector is often explained by the historical importance of the aviation industry for national security. Military equipment sales account for 20% of the turnover of the aircraft manufacturer Airbus and a full 50% of Boeing’s turnover. The two corporations dominate international aircraft construction and airplanes built by them are responsible for as much as 92% of air traffic emissions.

Many countries justify their refusal to regulate their aviation sector by pointing out that the reduction targets of the UN climate agreement refer to the emissions released within the borders of a country, which would not include aviation. This argument is inconsistent: after all, many of a country’s products are exported and their emissions are still allocated to the country of production. The tanked kerosene in a country could easily be measured and taken into account. The limited regulation is one reason for flights being so cheap in comparison to other modes of transport.

Read more:

- Heinrich Böll Foundation (2018): The Illusion of green flying

- Transport & Environment (2016): Aviation emissions and the Paris Agreement

- Carbon Market Watch: Aviation

- Scientific Article (2019): International and national climate policies for aviation

- Report by Stay Grounded (2017): The Illusion of Green Flying

Why is flying so absurdly cheap?

The tax privileges of the airline industry

A major reason for low ticket prices is that tax money contributes to making flying so cheap. Everyone – including those who don’t fly – pays for an incomprehensible tangle of subsidies, tax exemptions and public investments in order that the most polluting mode of transport remains cheap.

While the aviation industry is making ever greater profits, the pressure on its employees is mounting. Quality and safety are decreasing, stress and burnout are on the rise. Qualified staff are increasingly being replaced by inexperienced, cheaper part-time workers. Especially in low-cost carriers, the model goes at the expense of employees.

The by now largest European airline Ryanair has therefore faced protest by trade unions. The company shops around for the weakest contracts in the EU, outsources labour through agencies and bogus self-employment schemes. Ryanair also uses the strategy of aggressive union busting and hostility to the rights of workers to organise, speak up and seek representation free from victimisation and reprisal. After a big campaign, the struggle against Ryanair was partially successful.

Read more:

- Article by Stay Grounded (2019): Eliminating Tax Exemptions

- Article by Transport & Environment (2019): A cheap airline ticket doesn’t fall from the sky

- Campaign by the Federation of Trade Unions: https://www.cabincrewunited.org/

Which political changes do we need?

There are numerous ways to tackle aviation. Attention needs to be paid on just measures: It’s not fair to only raise prices for plane tickets, allowing only wealthy people to fly. How to reduce flying in a just way was the topic of a Stay Grounded conference held in July 2019 in Barcelona. The results can be read in the report “Degrowth of Aviation”.

What happens when airports increase?

Hundreds of new airports or airport expansions are planned to fuel the skyrocketing growth of the aviation industry. There are 550 new airports or runways planned or being built around the world, plus runway expansions, new terminals etc, totalling more than 1200 infrastructure projects.

Most of them involve new land acquisition, the destruction of ecosystems, displacement of people and local pollution and health issues. Noise, particles and ultra fine particles are a major issue for residents living nearby airports. More and more airports, especially in the Global South, are becoming ‘Aerotropolis’, or Airport Cities, surrounded by commercial and industrial development, hotels, shopping malls, logistic centres, roads, or connected to special economic zones. Those projects are often related to human rights violations.

Airports represent a main infrastructure for the globalised capitalist economy, needed for the just-in-time production and trade of goods, work travel, the tourism business, as well as the deportation of unwanted ‘travellers’: illegalised migrants. Effective resistance against airport projects can prevent cementing an emissions-intensive, destructive form of mobility for decades into the future.

This map brings together case studies documenting a diversity of injustices related to airport projects across the world. It was developed in collaboration between the Environmental Justice Atlas and Stay Grounded. For more information, or in case you want to contribute with information on a local airport struggle, please contact: mapping[at]stay-grounded[dot]org

What's the impact of military aviation?

Military aviation emits significant quantities of emissions during production and operation. Owing to the scarcity of independent, public studies on military fuel consumption, it is hard to get exact figures. It is estimated that military aviation accounts for 8% to 15% of this total, with military expenditures on the rise.

Military emissions have evaded critical United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) review for decades and continue to be exempted from international climate obligations in practice. Although military aviation can be argued to fall under Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), the reluctance shown by countries to report fuel use in these sectors means that military aviation emissions are effectively left out.

The impact of military aviation however goes much beyond its climate impact, with devastating effects of wars on people. Accounting for its emissions would be an important step. However, it is still far away from the wish of actually reducing or abandoning military aviation, weapons and war for fighting the climate crisis and building a peaceful world.

Read more:

Article by Stay Grounded: A Tradition of Camouflage

Study by World Beyond War: Demilitarization for Deep Decarbonization